For those of you with no interest in making your own liquid soap, you can stop reading now. Next week we’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programing of gardening, homesteading and cute animal pictures. Wink.

Edited 4/25/15 to add: This blog is MY opinion and MY experience with liquid soapmaking. I’ve had several readers point out that they have had different experiences from mine (with adding salt to thicken, and with the Soaping 101 glycerine liquid soap video, for example). Please note: YOUR MILEAGE MAY VARY. Feel free to experiment! Please share your differing experiences and understanding of the chemistry in the comments. That’s how we all learn from each other. This isn’t meant to be the final word on the subject. It’s just my own personal understanding and experience.

Questions about how to get started with liquid soapmaking come up a lot on some of my soap making groups, and I remember how hard it was to get a handle on it all when I started making my own, despite the fact that I’d been making cold process bar soap for years. I find myself writing out long-winded answers over and over again. So I thought I would do a bit of a brain dump on some of the fundamentals to get new liquid soapers started. Note: what this is NOT is a step by step guide to making liquid soap. If I were going to do that, I’d write an ebook. Also, apologies for lack of pictures. This is mostly an informational post.

The first thing you need to understand is that making liquid soap is not like making cold process bar soap. Had I understood this when I started, it would have saved me a lot of mistakes.

- It uses a different lye (potassium hydroxide – KOH, not sodium hydroxide).

- It’s a hot process soap, most easily made in a crock pot (though there IS a camp of people who make it cold process).

- It’s next to impossible to superfat liquid soap, because any unsaponified oils will simply float on top of the soap, because…you know…its a liquid, and mostly water, and oil and water don’t mix. There is no solid soap salt matrix to hold those extra unsaponified fat molecules in place like there is with bar soap. Therefore liquid soap won’t leave a conditioning layer of oils on your skin. Which leads to…

- The lye calculations need to be handled differently. Because you can’t really superfat, there is less room for error with your calculations. Too much lye and the pH will be too high, requiring neutralization. Not enough and you have left over fats floating on your finished soap. The lye is also less pure than with NaOH, making the calculations extra tricky.

- In order to get the lather you want (especially if you have hard water) you’re gonna need more coconut oil than you would use in bar soap. However, the “suggestion” for bar soap to keep your percent of coconut under 25% does not apply. I personally prefer my recipes to contain 40 to 45% coconut for lather.

- The consistency will not be like store-bought liquid soap. In order to get it to function properly, it needs to be quite dilute (though different oils need different amounts of dilution, which further complicates things). Think watery. If you’ve ever used Dr. Bronner’s Liquid Soap (a national natural liquid soap brand that’s been popular with the “natural foods” crowd since the 1950’s) you’ll understand what I mean by watery. This is always the most surprising thing for newbies to understand (it certainly was for me) when you make your first batch.

- Oils that contribute to “hardness” in bar soaps – like palm or tallow, really aren’t necessary in liquid soap (though you can certainly use them) as hardness obviously isn’t a factor with liquid soap.

I’ll address these facts, and how it affects how you make liquid soap, in the paragraphs below.

But first, references and where to get started.

The so-called “bible” of liquid soapmaking is Cathorine Failor’s “Making Natural Liquid Soaps“. It was published in 2000 and so is now 15 years old. I have a copy. It’s a lovely book, from a graphic design standpoint, and it contains some important beginner information about liquid soap making, like what oils will cause cloudy soap and how to thicken soap with a borax solution. But the techniques are overly complicated, passé, and the book is horribly organized. Step by step instructions on how to make liquid soap starts on page 22, the information on diluting your soap paste starts on page 41, the information on how to neutralize your soap (more on that below – it isn’t always necessary) is on page 42 – but the info on making the neutralizing solutions is on page 30, the recipes start on page 52, and no guidance is given for how long each recipe needs to cook, or how much each recipe needs to be diluted. You end up flipping back and forth through the book in a panic as you make soap, or underlining and flagging different sections (which is what I did). So, my advice is, check it out at the library and make some notes from it, but don’t bother purchasing it.

The so-called “bible” of liquid soapmaking is Cathorine Failor’s “Making Natural Liquid Soaps“. It was published in 2000 and so is now 15 years old. I have a copy. It’s a lovely book, from a graphic design standpoint, and it contains some important beginner information about liquid soap making, like what oils will cause cloudy soap and how to thicken soap with a borax solution. But the techniques are overly complicated, passé, and the book is horribly organized. Step by step instructions on how to make liquid soap starts on page 22, the information on diluting your soap paste starts on page 41, the information on how to neutralize your soap (more on that below – it isn’t always necessary) is on page 42 – but the info on making the neutralizing solutions is on page 30, the recipes start on page 52, and no guidance is given for how long each recipe needs to cook, or how much each recipe needs to be diluted. You end up flipping back and forth through the book in a panic as you make soap, or underlining and flagging different sections (which is what I did). So, my advice is, check it out at the library and make some notes from it, but don’t bother purchasing it.

Next up, a visual/blog liquid soap tutorial from Chicken In The Road. This is often cited as the best online tutorial around on liquid soapmaking, and it IS very well done. Don’t want to buy a book. THIS is your resource. My one quibble with it is that she mentions being able to superfat your soap with castor oil. You can’t. What she means to say is that you can superfat your liquid soap with Red Turkey Oil, aka Sulfated Castor Oil, which dissolves in water. This has been pointed out several times in the comments, and I really wish she would edit the original post to change that, as it is really confusing to newbies. FYI, there ARE other oils that have been chemically altered to make them dissolve in water. Shea butter is one. They too can be added to superfat liquid soap. I’ve never personally tried any of them.

There’s a new book on the market, only available directly from author Jackie Thompson, called “Liquid Soapmaking“. I have not purchased it. I have heard that it is better than Failor’s book. If you only purchase one book on liquid soapmaking, this is probably your best bet.

There’s a new book on the market, only available directly from author Jackie Thompson, called “Liquid Soapmaking“. I have not purchased it. I have heard that it is better than Failor’s book. If you only purchase one book on liquid soapmaking, this is probably your best bet.

A lot of the information I’m sharing here I learned from the Yahoo LiquidSoapers group, and the spin off Facebook LiquidSoapers group. Sometimes the best resource is other people to whom you can ask questions as they come up. I recommend either group. The Yahoo group has more information in their files. The Facebook group is more immediate and gratifying and you can easily post pictures.

Understanding the Lye Calculation

So potassium hydroxide, aka KOH, is the lye you use to make liquid soap. When turned into a soap salt by mixing with oils, it has a different chemical structure than when you do this with sodium hydroxide (the lye used to make bar soap). This gives your soap a different consistency. THIS is why those DIY recipes for grating up a bar of soap and adding water to “make your own liquid soap” result in soap the consistency of snot, rather than what you were expecting. Sodium hydroxide soaps want to be solid. Potassium hydroxide soaps want to be liquid. So, first up, make sure you have the right lye.

Catherine Failor’s technique for making liquid soap uses an excess of KOH. This was partially because liquid soap could not be superfatted or you’d have excess oils floating on top of your soap. It was also based on an understanding that KOH (potassium hydroxide) is only about 90% pure (the rest is mostly water that is chemically bonded to the molecules). This impurity makes calculating the lye tricky.

In the ensuing 15 years since Failor’s book was published, home crafters pushed the boundaries because 1) neutralizing is a pain in the you know what 2) they better understood how to calculate the lye correctly, taking into consideration the impurities and 3) they REALLY wanted to be able to superfat, even if it was just a tiny bit, to make a more conditioning soap.

So…with the lye calculated correctly, you do not need to neutralize, and if you neutralize anyway, you may push your soap backwards and break the molecules holding the soap salt together and end up with useless goop. But, with excess lye in the batch, if you don’t neutralize you could have a super high pH highly irritating unsafe soap.

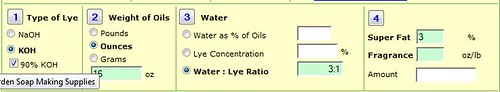

This is a screen shot of SoapCalc.net and how it should look when you make liquid soap (note: the weight of oils is up to you). Be sure to not leave the settings at the default, which is for cold process bar soap, not liquid soap.

The moral of the story is you need to know how to calculate your lye correctly depending on what you want to accomplish. Most people find that when using SoapCalc, checking the KOH box AND the 90% pure box, and then setting your superfat to +2 to 3%, you do NOT need to neutralize your resulting soap, yet you won’t have excess oils floating on top! Brambleberry’s lye calculator and the one from Summer Bee Meadows also take into consideration the lye impurity (there is no 90% box to check), but note that each calculator will give you slightly different lye amounts (frustrating). You may need to do your own experiments to see what works for your recipe. I personally prefer SoapCalc.

When starting out, keep your total oil weight to about 16 oz. This helps you avoid costly mistakes. My first batch of liquid soap made several gallons of finished product, that I scented all with the same fragrance. It literally took me years to use it all up. I will never scent anything with apple-cranberry again!

The Glycerine Method

About the time I joined the yahoo liquid soap group, everyone was all aflutter about the glycerine liquid soap method. With this method, instead of dissolving your KOH in room temperature water, you dissolve your KOH in very very hot (200 degrees) glycerine. Then you proceed as usual. (Note, glycerine is also a byproduct of the normal soap making reaction: oil + lye solution (lye and water) = soap salt + glycerine. This method adds additional glycerine beyond what is made in the soap reaction). This method has two benefits. Because glycerine is a solvent, it makes the soap reaction happen much faster, cutting down your trace and cook times. It also makes stirring the resulting cooking soap paste, rather than just mashing it around, actually possible.

An example of this method can be found in this Soaping 101 video. (A few notes on this video – she uses a 2:1 glycerine to KOH for her lye solution. Convention is to use 3:1. If you watch carefully during the pour, you can see that her solution still appears chunky with KOH flakes – yikes! I’ve also found this recipe to have almost zero lather in my hard well water. As this is a Bastile recipe – yes, she calls it a Castile, but its not, as Castile would be 100% olive oil – and less than 10% coconut, this isn’t that surprising. But I don’t recommend it unless you have super sensitive skin and/or a water softener).

Turns out mixing a highly caustic substance on my stove, heated to 200 degrees, makes me incredibly nervous. Lye fumes in the house. A substance that, if spilled or splashed, could cause both heat and chemical burns. I’m brave, but I’m not that brave. I tried it. Once. There are also some who think that excess glycerine makes a soap more drying. We don’t need that, as we’re already fighting that by not being able to superfat as it is. Plus, glycerine adds to the cost of the soap. So my personal compromise is to dissolve my KOH in 2x its weight in water, stirring until fully dissolved, then adding the additional 1x KOH weight in liquid vegetable glycerine, and proceeding as usual. (I mix my lye solution outside, while I’m standing upwind.) I feel like this gives me the best of both worlds. Experiment as you wish.

The Cook

Use a crock pot. Seriously. The whole double boiler method that Failor uses…ugh. Way too much work. You can buy used crock pots at thrift stores for next to nothing. Buy one just for making soap. I stick blend in my crock (off and on if its taking a long time to come to trace) until the mixture is too thick to stick blend any more. Then I stir it about every 15-30 minutes, while keeping the heat on low. DO remember to stir (or really, mash about – soap paste is so thick its like silly putty – its next to impossible to actually “stir” – another thing Failor doesn’t really tell you in her book). It can climb up the sides of the crock and spill otherwise. After an hour or two it will stop doing that. Note that depending on the oils used, it can take 8 to 10 hours to fully cook your soap! I start doing small clarity dilution tests after about 3 hours.

Testing for Excess Lye

You’ll see information on diluting a bit of soap paste in water and observing it for “cloudiness” or “milkiness” to see if your soap is done cooking (testing for unsaponified fatty acids). This is all well and good, but depending on the oils you used, it may never test clear, and if you have excess lye (accidentally or on purpose) you won’t know it from this test. So, I highly recommend buying some 1% phenolphthalein dissolved in ethanol. You can find a couple of ounces of it on Amazon for around $10 and it will last you a LONG time. Phenol is a pH indicator. You put a drop of it on a bit of your soap paste (removed and put into a separate container) and it changes color, from light pink to deep magenta, in a pH range from 8.2 to 9.8 (darker = more alkali). No color change or only a very slight color change and your soap is fine. Big color change and your soap needs to be neutralized with a borax or citric acid solution (carefully, adding only a little at a time – remember, too much – especially of citric acid, and you will break the soap salt bonds and end up with goop). Potassium soaps naturally fall into the 9.5 to 10 pH range. Interestingly, Failor’s book talks about using Phenol, but doesn’t tell you the pH range it tests for. pH strips are useless. Don’t buy them. Don’t rely on them. If you have a pH meter, by all means use that, noting that your soap needs to be quite dilute for it to read accurately.

Dilution

One of the best tips I ever got from the yahoo group was to dilute your soap paste starting with 2x the weight of the OILS in the recipe, not the paste weight. Paste weight is hard to estimate. You have to remember to weigh your container before hand, so you can weigh your container and finished paste at the end. Some of the water you used is going to evaporate off and you need to know how much has been lost. You need to account for any paste removed for doneness testing and/or phenol testing. It becomes a math nightmare. But the amount of oil used doesn’t really change – except for the small percentage removed for testing.

How do you know when you’ve diluted your paste enough? One, the paste will be fully dissolved. This can sometimes take up to 24 hours, so have patience. No more chunks floating around in there? Good. Now, is there a skin forming on the top of the diluted soap? Kind of like the skin on a pot of boiled milk that has cooled on the stove? Then you need to add more water until no skin forms. Hot soap will not form a skin while room temperature soap will, so it needs to be cool to know if you’re gonna form a skin, but warm soap/water will dissolve faster. Different oils take more water to fully dilute. You can always add a bit more water, but its a pain to heat your soap to evaporate off water if you have added too much. Start conservative, have patience, and add only a little bit more at a time (say, 1/8 cup) until you stop forming a film on top. If the soap seems too concentrated at this point, i.e. its hard to wash off your hands, you can always continue to add more water. Keep very good notes.

Neutralizing If You Need To (taken directly from Catherine Failor’s book)

- Borax (20 Mule Team – NOT Boric Acid) 33% solution: 3 oz borax dissolved into 6 ounces of boiling distilled water. Borax is a buffer and can also be used to thicken liquid soap. Some people love it. Others aren’t comfortable using it. Great blog post on its safety here.

- Citric Acid 20% solution: 2 oz citric acid dissolved into 8 oz of boiling water.

For one pound of soap paste – diluted with water to appropriate final consistency (you can’t stir your neutralizer into your paste – its too thick and it won’t disperse), add 3/4 oz (approx. 1 1/2 tbsp) borax or citric acid solution, as described above. Stir well. Test again with Phenol (always by removing a sample – never directly into your soap). Add more solution in smaller increments if necessary. It’s easier to over do it with the citric acid. Maybe start with half the amount recommended by Failor, and add more if necessary. Her recipes were purposefully lye heavy.

Clarity

Failors soap book, and other references around the internet, will have you believe that clear liquid soap is the holy grail of soap making. That somehow clarity equates to quality. I have NO idea where this idea came from. I personally could not care less. We all grew up with opaque pearlized soft soap and never blinked an eye at its lack of clarity. The following oils will make clear liquid soap: Almond, Canola, Castor, Coconut, Olive, Palm Kernel (a sub for coconut), and Soybean. There are probably others (sunflower, apricot kernel…). Oils that will result in a somewhat to quite cloudy soap are palm, tallow, lard, jojoba and most butters. This likely has to do with the fatty acid make up of the oil, along with the unsaponifiable components. If you really desire crystal clear liquid soaps, only use the oils that produce them, and then also sequester your soap for 2 weeks to a month after its diluted so any unsaponified substances have time to sink to the bottom or float to the top. Then somehow carefully decant JUST the clear soap, leaving the rest behind. Good luck. Grin. Again, I think crystal clear soap is WAY overrated. I’m much more interested in how it feels on my skin.

This particular batch was made with Palm Kernel, Lard and Castor oil. Note – gasp – it’s not clear. Turns out I DON’T CARE, LOL.

Thickening

After the basics, this is probably the most common question asked on liquid soap making groups. “How do I thicken my liquid soap?” We all want our soaps to be the consistency of the soft soap we remember from our childhoods (but heaven forbid it not be clear – go figure). There are a variety of answers. I am personally OK with watery liquid soap, so I have not tested most of these. I simply put my liquid soap in foamer bottles. Problem solved. I’m also trying to keep the list of ingredients to a minimum, and to substances most people would recognize. If you do play with these possibilities, be sure to follow the manufacturer’s suggested directions and use rates.

- Borax – as discussed above, or in higher concentrations. Seems to be a bit hit and miss. I’ve had it work quite successfully with a coconut (15.5%), canola, olive and castor formula.

- Salt – 1/2 oz table salt dissolved in 1 1/2 oz warm distilled water. Add 2 tsp per pound of finished soap to start. Reportedly doesn’t work with soap that is more than 20% coconut. Also may make your soap somewhat pearlized.

- HEC, Hydroxyethylcellulose. Can be used up to 1% as a thickener. Will feel slimy if too much is used. Add to dilution water at room temp. Then slowly heat water to fully dissolve. Then use it to dilute your soap. If not dissolved properly, produces “fish eyes” of undissolved HEC.

- HPMC, Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose. Add to boiling water and stir occasionally. Thickens as it cools. Can be added to liquid soap that is already diluted and is too thin (add directly to diluted HOT soap). Use at around 1% of dilution water.

- Liquid Crothix. Add directly to soap at room temp. 1-8%. I’ve seen good things reported. I have not tried it.

There are also liquid soap recipes that use a mix of KOH and NaOH in order to achieve a thicker liquid soap without additional additives. The starting ratio seems to be 60% KOH and 40% NaOH. I have NOT tried this method. Please do your own research on this technique, and let me know the results! Note, adding NaOH will compromise clarity.

Preservatives

This is a hotly debated topic in the liquid soap world. There are those (including Failor) who say that the pH is high enough that nothing nasty is going to grow in there (it should be noted that Dr. Bronner’s soap does NOT contain a preservative). There are those who say that water = medium for nasties to grow, and a preservative is necessary. There are those who say that they are only needed when the soap is diluted enough for a foamer. There are those who say that you should never ever use anything but distilled water for your dilution (THIS I agree with). No teas, no goat milk, no aloe etc. – though there are methods for using these substances in your soap PASTE – I have not tried them. I don’t personally add a preservative to mine. If its good enough for Dr. Bronner’s (again, been in the market place since the 1950’s), its good enough for me. But its a decision you should research for yourself. It is difficult to find preservatives that are effective at a pH higher than 8. This is a good overview of what’s available.

So, after all of this learning and experimentation, I have found that liquid soap does not sell as well for me at market as my bar soap does. I thought for sure I’d be winning over new customers who don’t like to bathe with bar soap when I added it to my line. But this has not proven to be the case. I think a lot of this is cost. My packaging on my bar soaps cost me pennies. My packaging on my liquid soaps costs me dollars. There’s a bit of sticker shock involved when compared to big box store products that are so inexpensive. I make a few batches a year, for our own use in soap dispensers around the house, and for the small group of my customers who really do prefer it. But it hasn’t turned out to be the niche market I had hoped it to be. Hopefully my experience will not be yours.

Miles Away Farm Blog © 2015, where we’ll be introducing “soap saver socks” at this year’s market, which hold a bar of soap for ease of use and drainage, with the added benefit of being in an exfoliating wash cloth at the same time. Hopefully this will convert the “commercial shower gel” users to try hand crafted soap!

Miles Away Farm Blog © 2015, where we’ll be introducing “soap saver socks” at this year’s market, which hold a bar of soap for ease of use and drainage, with the added benefit of being in an exfoliating wash cloth at the same time. Hopefully this will convert the “commercial shower gel” users to try hand crafted soap!

42 comments

Comments feed for this article

April 23, 2015 at 5:05 am

Teresa Moss

Great “brain dump”! I didn’t have any luck with the liquid soaps at my market either.

April 26, 2015 at 5:00 am

Kristi

This was awesome. You have the knowledge and experience to write your own book. You could do one for both types of soap making!

April 26, 2015 at 5:08 pm

Nancy Crt

I stumbled across your article. Great information and I agree with all you said. I have Jackie’s new book and it is great! I am still pondering some of her comments regarding “superfatting” LS. I like a lot of soapers SF at 3% and don’t have oils floating. So it could be my KOH is purer than 90%. But her book is much easier to follow than Failor’s. She does refer to Failors a lot. I too am on yahoo group and Facebook group. Both have their pros and cons. Thanks for writing this. I will refer new soapers in yahoo group to this article. Nancy

April 26, 2015 at 5:21 pm

MilesAwayFarm

Many thanks Nancy. It’s an ongoing learning process for all of us. We’ve come a long way in 15 years.

April 27, 2015 at 6:28 am

Cee Moorhead aka Zany in CO

Excellent! Bravo! (applause emoticon here)

April 27, 2015 at 8:12 am

MilesAwayFarm

Thanks Cee (aka Zany). I learned SO much of this from you!

April 29, 2015 at 2:18 pm

DeeAnna

“…note that each calculator will give you slightly different lye amounts (frustrating)….”

Yes, it is frustrating, but there’s actually a reasonable reason why the calcs give varying results —

Of the soap recipe calcs that I’ve checked, all are set to about 100% purity for NaOH. This is building in a hidden superfat for bar-soap recipes, since NaOH that soapers use is almost always not 100% pure. But as you note, errors like this are pretty much invisible when making bar soap.

Most of the calcs are set for 100% KOH purity as well, with three exceptions that I know of: SoapCalc (90% or 100%), Brambleberry (95%), and Summer Bee Meadow (94%).

The 90% purity setting is good for Essential Depot KOH. The 94-95% purity used by Brambleberry and SBM is good for Brambleberry KOH as well as The Lye Guy KOH. Other suppliers may be selling KOH with purity anywhere from 85% on up. Ask before you buy to make sure you know what you’re getting.

My suggestion when creating a liquid soap recipe is to check the purity of the KOH you are using and choose the calc that is based on the KOH purity closest to what you’re actually using. By choosing the “wrong” calc for your KOH, you could end up with liquid soap that is lye heavy or fat heavy —

Example 1: You use Soapcalc set at 90%, set the superfat at 3%, and use 95% pure KOH. Your soap could have about 2% too much lye (lye heavy).

Example 2: You use a calc set for 100% KOH purity, set the superfat at 3%, and use 95% pure KOH. Your soap could have an actual superfat of 8%. This excess fat may make the liquid soap cloudy and may even separate from the soap after dilution.

Sometimes your KOH purity may be quite different than what any of the calcs are based on. So another way to correct the KOH purity is to use the calc you like best and adjust the KOH weight to correct for the purity of the KOH you are using —

KOH you need = (KOH based on calc’s purity) X (Calc’s KOH purity) / (Actual KOH purity)

Example 3: You use SBM calc which is set for 94% purity. Your actual KOH is 85%. The calc says you need 145 g of KOH at its purity. The weight of KOH that you need at your actual purity of 85% is this:

KOH you need = (145 g) X 94 / 85 = 160 g

I hope this helps! –DeeAnna

May 7, 2015 at 3:31 am

Michele

Great article that breaks down many of the issues and components of Liquid Soapmaking. Thank you!

May 27, 2015 at 6:20 pm

Debi B

This article is a jewel. I can’t thank you enough for writing it.

October 11, 2015 at 7:53 pm

Karishma c jain

Is there any other option, other than double boil or a crocpot method to make soap. In India we don’t hv crockpot and double boil takes a lot of time. Is an induction stove feasible or a gas option. Your sharing has made my soap making an easy affair. Thank u.

October 12, 2015 at 8:19 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Karishma. There are those who have had good luck with making liquid soap “cold process”. They heat it and blend until its too thick to stir, then turn off the heat and let it sit for several WEEKS until it finishes reacting. I personally have not had good luck with this. The problem with just a stove top direct heat is that it will get too hot and boil over. Liquid soap tends to puff up pretty easily. Not very hard to make a double boiler. Just put one large pot inside another large pot. Bottom pot gets water. Water, boiling, never gets over 100 degrees celsius. You could try it in an oven, if you could keep your oven temperature very low (under 76 c), and stir frequently. Good luck.

October 12, 2015 at 10:09 am

Cee Moorhead aka Zany in CO

Thanks for the compliment, Jennifer! 😀

Cold Process is the easiest way to learn how to make LS — especially for those with a background in making CP hard bars. The process is essentially the same, only you don’t cook the soap. The difference is, TEMPS ARE IMPORTANT. Using normal technique, and following safety guidelines, combine when oils are 160°F (71°C) and lye solution is 140°F (60°C). Stir by hand, then SB (on and off) to trace 10-15 minutes over LOW heat. Maintain temp at 160°F (71°C) until trace occurs. Let sit 5 minutes off heat to make sure it doesn’t separate. If it starts to puff up, that’s a good sign! But BE PREPARED. Quickly move it to the sink and stir it down. Cover and CURE 2 WEEKS just like you would do hard bars.

November 13, 2015 at 6:02 am

Brandi

Just a note on thickening… I’ve had success thickening with guar gum and xanthan gum. I always add 2% glycerin to my diluted LS because I like the emollient properties it adds, and mixing a bit of gum in the glycerin prior to mixing into the diluted soap thickens it nicely and prevents lumps. They can cause a little cloudiness, so if you desire a clear soap, use cosmetic grade xanthan gum. A soleseife version of LS also produces a nice thick product… Use a sea or kosher salt brine as your lye liquid. In my experience it doesn’t affect the lather and makes a very thick, easy to dilute LS.

July 7, 2016 at 9:38 pm

sally

Hi. Thanks for the info. I have been making hard cp soap for my family for the past 5 years and I thought I would attempt LS. I have both books that you mentioned and I was a member of the yahoo liquid soapmaking group (but i think i’ve been kicked off for not putting any posts up). I made a liquid soap using the paste method in the slow cooker, everything went according to plan but then the neutralizing threw me out. In hindsight I don’t think it needed neutralizing because the ph was 9 and it looked ok. I used Catherine Failors method with the citric acid, the diluted soap was cloudy with a milky top. I left it to sequest for 3 weeks and decanted the clear soap into another jar. I was really puzzled because it had a milky top and a milky bottom (where i guess the oil had settled). The other puzzling thing was the LS changed from cloudy to clear every few days. Is this normal?

I used mango butter, avocado oil, coconut oil and castor bean oil.

Anyway after reading your post it made me feel like less of a failure in regards to the cloudy LS and will have another go at LS

Still confused

Sally

July 8, 2016 at 5:59 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Sally. Yes, you probably neutralized when you didn’t need to. Also, most oils that are solid at room temperature (ie mango butter) are going to cloud your soap due to the fatty acids they contain. Doesn’t make it bad, but it will make it cloudy. So some of your cloudiness might have been from using the mango butter. Good luck.

July 8, 2016 at 4:56 pm

Nancy C

Hi Sally, I am one of owners of liquidsoapers group, you don’t get kicked off for not posting. Some members never post. If you are having problems with posting or getting posts please let me know.

September 2, 2016 at 12:50 pm

Rosalia Worell

I would like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this website. I’m hoping the same high-grade site post from you in the upcoming as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my own site now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings fast. Your write up is a good example of it.

September 2, 2016 at 7:05 pm

MilesAwayFarm

Awww, thanks Rosalia!

November 7, 2016 at 9:34 pm

Debi

Hi MilesAwayFarm, this is the best article I’ve seen on LS, it covered many of my questions with info I couldn’t find elsewhere. I just made my first batch of LS and didn’t realize SoapCalc automatically added a 2% superfat. Is there anyway I can fix it? Also, I used the glycerine in place of water method, but when I was mixing it up, it turned into a very thick white paste, not a clear liquid. What did I do wrong? Thanks again for your help,

November 8, 2016 at 7:33 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Debi. SoapCalc doesn’t automatically add a 2% superfat. Where did you get that idea? YOU can calculate at +2%, while also checking the 90% KOH box, and not have to neutralize (that’s what I do). But the superfat is whatever you set it at.

When you say “thick white paste” are you talking about your KOH/glycerin mixture? If so, that’s normal. If that the end result, after the cook and dilution, then its either the choice of oils you used (some will make a cloudy soap) or you haven’t added enough water yet. Or…if you’ve already added fragrance, some fragrance oils can cause your liquid soap to go cloudy as well. Give the post a second read through, and let me know how you come out in the end. Good luck!

November 9, 2016 at 6:53 pm

Debi

Thanks, great advice. I did have to add more water and it actually turned out ok, no oil floating on top and a fairly good viscosity. Would you suggest additng a preservative to this soap since we dilute it with water? Just as an FYI, everytime I open SoapCalc it automatically has 5% super fat filled in, along with 5% FO, 38% water, and 1 lb recipe. Isn’t that the way its supposed to be? I have to manually change them. I will definitely use the 90% KOH option next time.

November 10, 2016 at 9:17 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Debi. Yes, you ABSOLUTELY need to change the default in soapcalc when making liquid soap. The default is for cold process bar soap and is totally wrong for liquid soap. That screen shot above, of SoapCalc with the KOH box checked, the 90% box checked, the water lye ratio at 3:1 and the superfat at 3%? THAT’s what you want it to look like. I’ll go in and edit with a caption to make that more clear. Thanks for pointing that out! I’m glad your soap came out! Preservative is a hot issue in the liquid soap world. Some say absolutely yes. Some say it isn’t necessary because of the high pH. I’m in the not necessary camp. I look at the national natural liquid soap brand, Dr. Bronners, which has been around since the 1950’s. They do NOT add a preservative. I figure if its good enough for them its good enough for me. But do what YOU feel comfortable with. Note that its actually difficult to find a preservative that works with liquid soap, as most preservatives don’t work will in high pH environments.

December 28, 2016 at 11:13 am

Marina Miletic

Thank you Miles Away Farm for this excellent post and for sharing your personal experience making and selling liquid soaps! This was a great article. I just have a small suggestion to modify a typo. The normal soap making reaction is:

Oil + Aqueous (Dissolved) Lye => Sodium fatty acid salt (Soap) + Glycerin

To be totally nerdy and pedantic, the reaction is more accurately:

Oil + 3 NaOH => 3 Sodium fatty acid salt (soap) + Glycerin

There is no need to list water because it is not technically a reactant and does not change before or after the reaction.

Anyway, that’s enough chemistry for today. Thank you again for this wonderful article.

January 1, 2017 at 9:14 am

MilesAwayFarm

Marina, thanks for noticing the typo where I left the oil out of the reaction. I fixed that! And you are SO right. The water is only a reactant (catalyst). But, its hard enough for non chem people to get their heads around chemical reactions as it is, and we all know you NEED water in order for the reaction to proceed. I’m not writing for chemists. I’m writing for non-chemists who need to be able to understand what’s happening on a chemical level. So therefore, I’m comfortable leaving the water in, even if this is not technically how a chemist would write the reaction. Thanks for reading!

January 8, 2017 at 1:26 am

Emma

hello there, i seen a clue in this blog…can i heat liquid soap to evaporate some water off? also the gum stuff wouldnt bacteria love that?

January 8, 2017 at 2:44 pm

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Emma. Yes, if you have added too much water, you can slowly heat your soap to evaporate off some of the water. But remember. 1) liquid soap, by its nature, is going to be more liquid than the stuff you are used to buying in the store. 2) if it forms a film on top, it needs MORE water – so you might get it to just the consistency/viscosity you want only to realize that it is too concentrated and keeps forming a film. I don’t know what you mean by the gum stuff. Do you mean adding one of the thickeners I mentioned, I don’t know. I DO know that the pH remains really high, which is detrimental to a lot of nasty things, making it hard for them to grow. If you feel more comfortable using a preservative, by all means add one, but keep in mind it must be one that will work at a pH of around 10.

February 20, 2017 at 5:10 pm

Silke Boker

Thank you for that great article. I have read it I don’t know how many times before I finally made my own LS. I thought all had turned out well until today when I bottled it up and noticed that the soonest I add water to it for washing the clear soap turns all cloudy. Do you have any idea why? I used coconut and sunflower oil only. No EOs or FOs. I had it sitting for about a month sequestering.

February 20, 2017 at 8:42 pm

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Silke. Are you talking about when you add water to it to dilute it? Or when you squirt some into a sink full of water? If its the latter, ie a sink full of water, that’s totally normal. The been around forever Dr. Bronner’s soap does the same thing. Not quite sure why. Liquid soap will also cloud up when its cold, so if the water you are adding is colder than what’s in the bottle, that could be it too. I’d let it sit for 24 hours or so at room temperature and see if it clears up.

February 21, 2017 at 6:43 pm

Silke

Thank you for your reply. I guess I just didn’t expect having milky dish water 😉

April 11, 2017 at 1:26 am

Jacqueline Mitchell

Hi Thanks for your article, as someone trying to find a liquid/cream soap recipe that doesn’t need diluting – this was very helpful and you are the first useful site I’ve found on this. I have made a recipe for cream soap which does not need diluting to become a cream body wash, However the PH is 9.8 and it needs to be more like 5.5..I use a KaOH/NaOH mix, a lot of Stearic Acid and much more water than needed in the recipe and I cook for 2 hours. Do you think that more cooking would reduce the PH or is it a case of adding citric acid to bring down the PH – I’m in the UK with a small soap/cosmetics business.

April 11, 2017 at 6:33 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Jacqueline. The nature of ALL natural soaps made with KOH or NaOH is that they pH of the resulting soap (actually, chemically, the soap salts) is high. You can NOT lower a natural soap beyond about pH 8 without the actual soap itself coming back apart and resulting in “goo”. And the reason the soap is initially a thick paste is this allows the chemical reaction to happen in a timely manor. While the water acts as a catalyst to bring the fatty acids and the lye components together, it can also get in the way if too much is in there. Too much water and your reaction will be VERY SLOW. Not what you want. That is why liquid soap is a two step process. Make it the regular way, and then add as much water as is needed to make in into a workable fluid once you know the reaction is complete. Here’s a great piece recently published by Modern Soapmaking on pH, how to test it, why its important, and why the belief that we need a body wash to be at 5.5 is really a myth. Good luck! http://www.modernsoapmaking.com/how-to-ph-test-handmade-soap/

April 12, 2017 at 1:13 am

Jacqueline Mitchell

Thank you very much, this post and the article very helpful.

September 6, 2017 at 5:38 am

DiamondDee

Oh My Gosh! This was succinct and cut through all of the gobbley goop.

I have both books mentioned above and I am still confused. I want to make liquid soap with glycerin to speed the process but there were comments about separation down the road. What are your thoughts?

Also, in the Jackie Thompson book, she mentions discounting the water and replacing with glycerin to speed the process and then she mentions in all recipes after that to add in potassium carbonate which I am having a difficult time finding. Can you recommend that I can use the discounted water with glycerin and bypass the potassium carbonate? I tried reaching out to her for clarification and CANNOT find her anywhere and the email address listed for her doesn’t seem to work. I sure hope you are still replying to this post because i need an answer as I am so exhausted searching for answer and you nailed almost every single question I had. Thanks for that and for the forthcoming guidance.

September 6, 2017 at 6:21 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi DiamondDee. Glad I could help. I’ve never had separation using glycerin, though I’ve only done a 100% replacement for water in the cook once. As I mentioned, my standard recipe is now 2 parts water, 1 part glycerine to the amount of lye. This does speed the process somewhat, and makes stirring and dilution easier (though not easy 🙂 ) and doesn’t require the scary melting lye in glycerin on the stove bit. As for time savings, I make my soap in a crock pot. Other than that first hour of checking and stirring every 15 minutes or so, I just set it and forget it. I check every hour or so after the first hour until it reaches that translucent vaseline stage, and then start diluting. I leave the lid on, don’t really stir it, and it comes out fine. I don’t think you can really overcook it, other than drying it out. Use the lower heat setting and be patient. Hope this helps.

Jackie Thompson still shows up on the Soaping 101 Study Hall Facebook group. You might try tagging her there. Sorry she’s not responding.

I don’t actually have Jackie’s book and so am not familiar with her recipes. I’ve never used potassium carbonate. Failor’s book mentions it too, and I couldn’t find it either. You CAN purchase it at Save On Citric online – but you have to buy 5 lbs. My recipes seem to work just fine without it. Good luck.

October 9, 2017 at 7:03 am

DiamondDee

All of the information on making liquid soap, neutralizing it and thickening it has scared me to death. I found potassium carbonate, Borax as suggested to get me started. Every single day, I say I am going to make the soap and scare myself into not doing it. I was also uncertain about the testing of the soap and will use your method of clicking 90% and +2 for superfat. I have the liquid tester, I have a digital ph tester and the test strips (just to be on the safe side). I make tons of cp, cphp and hp soap but this one makes me nervous. I am going to go out on the limb and just do it. I will let you know how it turns out and thank you again for your guidance and reply.

October 10, 2017 at 6:48 am

MilesAwayFarm

Keep me posted, and good luck. As long as you get the chemistry numbers right, it will be safe. May not be the consistency or clarity you are seeking, but as long as it is isn’t lye heavy, what have you got to lose? It’s only soap. :-).

June 3, 2018 at 3:40 am

Kerrie Kelly

I have enjoyed this article a great deal. When adding more water because a skin is forming on top , can your soap be cold? And I guess you keep adding until a skin no longer forms? Many thanks

June 3, 2018 at 7:29 am

MilesAwayFarm

Hi Kerrie. Yes, your soap can be cold. In fact, its better if it is, because the skin may only form when its at room temperature. And yes, keep adding in small amounts (I’d wait a few hours after each addition) until you no longer get a skin.

December 31, 2018 at 1:40 pm

Jen

Thank you so much for your article. I too was wanting to try liquid soaps as all of my friends and myself use them. Have you tried reintroducing liquid soaps again? What is your favorite oil to work with in general? I like sweet almond oil lately! 🙂 Happy new year

December 31, 2018 at 5:24 pm

MilesAwayFarm

I like sweet almond as well. I have not reintroduced them. I do make it available as a special order if someone wants it, as I always have a batch on hand for our own use. But I’m too busy to make ONE MORE PRODUCT if it doesn’t just fly off the shelves. I’ve dropped a lot of things from my product line over the years, as I’ve narrowed in on what sells best for my customer base and area.

June 27, 2019 at 7:48 pm

Lois Deason Harris

I have seen several blog posts in the past by people who use their oven. I don’t have them marked because I use a crockpot, but you can find them by searching for oven processed soap.

June 28, 2019 at 6:51 am

MilesAwayFarm

Just to clarify, the recipes in Failor’s book aren’t in the oven, they are on the stove top.